1 When someone steals an ox or a sheep and slaughters it or sells it, the thief shall pay five oxen for an ox and four sheep for a sheep. 2 (If the thief is found breaking in and is struck dead, no bloodguilt is incurred; 3 but if it happens after sunrise, bloodguilt is incurred.) The thief shall make full restitution or, if unable to do so, shall be sold for the theft. 4 When the animal, whether ox or donkey or sheep, is found alive in the thief’s possession, the thief shall pay double. [Exodus 22:2-3, NRSV]

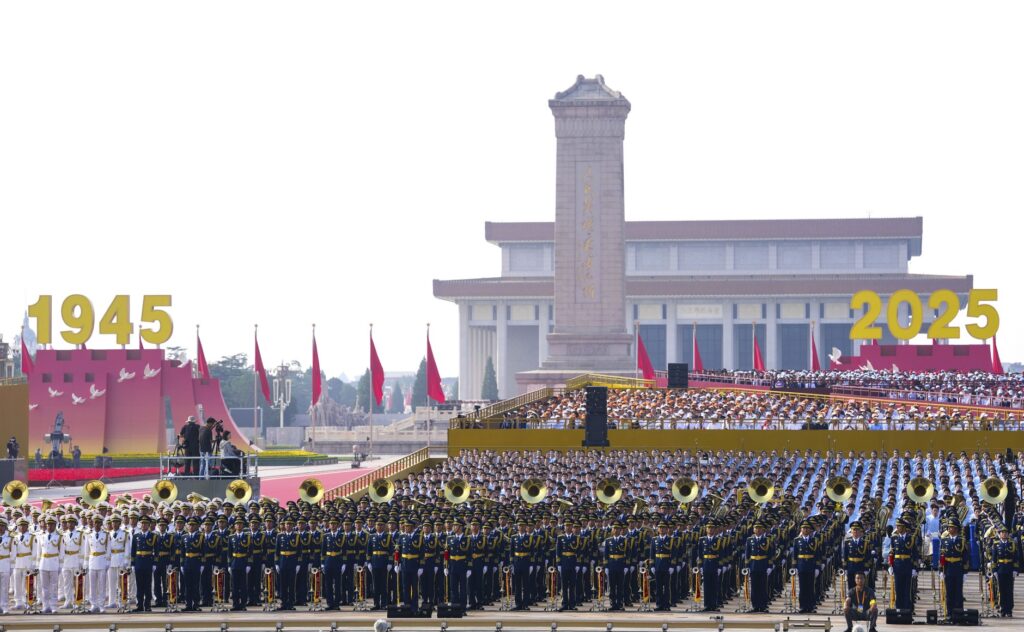

2025 China’s Victory Day Parade

2025 China’s Victory Day Parade

This post continues from post “353. A Look at China’s Victory Parade and World Peace” of 1 January 2026.

Thirdly, Japanese WWII atrocities must never be forgotten

Former German Chancellor Willy Brandt, demonstrating sincere reflection, earned global respect by kneeling in Warsaw for Nazi crimes. In stark contrast, Japan – a nation that committed parity if not worse crimes against humanity during WWII – not only erected monuments for Japanese war criminals, but also elevated the descendants of Class A war criminals to the position of prime minister. This fundamental difference in historical attitude is the root cause of China’s and surrounding countries’ disgust over all things Japanese. So much so, in fact, that it is no surprise to occasionally hear Malaysians of Chinese descent adamantly refusing to visit Japan, “even when I am offered a free trip.”

Unapologetic and American-backed, Japan is once again militarising itself in Asia. This will sabotage regional peace. This in part explains why China, a nation of 1.4 billion people, of superpower status in the contemporary world, is so united in adamantly insisting on exposing not only the Japanese aggression but their inhuman atrocities during the war. The major subtext in China’s September 3rd parade is to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the hard-won victory in the Chinese people’s war of resistance against Japanese aggression and the world anti-fascist war. This was the second time since 2015 that China has held such a military parade. Japan officially surrendered on Sept. 2, 1945, by signing the Instrument of Surrender. China designated Sept. 3 as Victory Day.[1]

East and South-East Asia as a whole is wary about Japan’s renewed aggression. Some standout reasons raise lasting concern:

- Germany had openly apologized, atoned, made amends and moved well into the future. Japan, and its emperor, has never fully confronted its atrocities, failed to apologise, and even embarked on a concerted effort at denial, thus remaining perpetually locked in the ugly past with its neighbours.[2]

- With a dwindling and paltry remnant of living Japanese survivors of the WWII, a misconceived political decision to conceal the truth of Japanese aggression and war-time atrocities in schools and published materials has effectively shielded young Japanese population from Japan’s violent history. Worse yet, the young are deliberately misled into believing that they are the victims living among belligerent neighbours out to get them. Even if they hear about the Japanese invasion of China, the Japanese under-30s generation lacks a healthy sense of history: “The invasion was undertaken by the previous generation. What has it got to do with us that we have to apologise?” Takaichi, the current PM, enjoys high approval ratings amongst the young generation precisely on this account. Historical repentance and lack of it marks the difference between the Germans and the Japanese. The Japanese young are insidiously shielded from Japanese shame and socialized into a false Japanese pride.

- Then, you have the perpetually troubling ritual of Japanese war-heroes worship, and the diplomatically disastrous practice of Japanese politicians, led by their prime ministers, annually matching in high profile to worship their war-heroes at their proud national war-heroes shrine. This is a Japanese sickness. Their open display of Japanese pride is as sinister as it is insulting to the neighbours they had so grievously harmed during the war. Blinding war crimes remain unatoned.

- Pacifism was written into the postwar Japanese constitution, and pacifism right after the war used to be an idée fixe of the bomb-stunned Japanese public. But now, Japan’s pacifism hangs in the balance, with a growing willingness in Japan to militarise. This is no doubt fueled by the lack of a national reckoning with Japan’s own wrongdoings. Politicians have been taking the lead to create an ominous shift. Former PMs Abe and Kishida had both openly pushed for more militarization, sending troops and lethal weapons to allies at war such as Ukraine, increasingly dividing the country over its commitment to post-war pacifist ideals. By 2027, Japan’s military budget will account for 2% of its GDP, and become the third-largest in the world. And America, the supposed “grand-victor” of WWII and grand “beacon of world liberty”, with its thriving military-industrial complex, and a major witness to the UN document barring Japan from rearmament, is egging Japan on, firstly to sell Japan more arms and, secondly, to equip Japan to help contain China. This insidious and selective historical amnesia, meshed into the habitual American hypocrisy, has potentially serious consequences which are too frightening to imagine.

- The current first-woman Japanese PM, Sanae Takaichi, who kicked off her new term with a disastrous proclamation of her desire to side with the independence-faction of Taiwan against China, is simply asking for trouble.[3] This is a veiled attempt to reinsert Japan back to the pre-WWII order where Taiwan was colonized by Japan. It is at the same time, a veiled attempt to reignite the aggressive militarism of pre-war Japan. Western media as usual reacted to the stern Chinese response with their selective historical amnesia, choosing to ignore Takaichi’s dangerously inflammatory rhetoric that drives regional tensions. These media do not mention that she had chosen “to use historically-loaded language that echoes Imperial Japanese invasion justifications” relative to Taiwan. They make no reference to the Nanjing Massacre, Unit 731 or the “comfort women”. Nor do they discuss the “Three Alls Policy” (kill all, burn all, loot all) that devastated Chinese villages. Nothing about the tens of millions Chinese civilian killed. Western media hypocritical silence on China’s legitimate historical core concerns is deafening.[4] Whatever the USA may or may not do to stop Japan’s dangerous rise in militarism[5], China will not let its population be endangered by passively sitting around. Furthermore, the return of Taiwan to China being a non-negotiable part of the post-WWII order, and sovereignty being the foundation of a nation, China will not and cannot “go easy”[6] on Takaichi who represents the aggressive fascist-imperialist face of Japan.

- Beijing scholar Victor Gao relies on a solid framework of historical jurisprudence in his debate with western thinkers. He pulls the Taiwan issue back into a dimension with historical depth. First, to counter the typical western allegation of Chinese aggression, he uses the term “unfinished civil war” to redefine the legal nature of cross-strait conflict, countering the hypocritical western narrative of Chinese aggression. Second, he invokes the still valid “enemy state clause” from the UN Charter, as a legal basis to issue a stern warning against any potential Japanese military intervention. Third, he skillfully turns the America’s own core national myth of unity based on Lincoln’s Civil War victory to question and challenge the West’s consistency and double standards on the issue of sovereignty.[7]

Spoken by a Chinese Defense Ministry spokesman, the following quote sets the record straight:

It is an ironclad fact that Japan was defeated in WWII. International treaties and instruments such as the Cairo Declaration, the Potsdam Proclamation, and the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, explicitly ban Japan from rearmament.

The international community must be on the high alert that in recent years, Japan has acted against this post-war order and attempted to break away from the restraints of its pacifist Constitution and brazenly expanding its military build-up, drastically increasing its defense budget, expanding the revision of its security policies, relaxing restrictions on weapons export, and trying to revoke the three Non-Nuclear Principles in the Taiwan Strait. These moves pose serious threats to regional peace and stability.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression and the World Anti-Fascist War. People around the world, especially those from China and other victimized countries in Asia, will never forget the catastrophe brought by the Japanese Fascists. The specter of Japanese militarism must never be allowed to haunt the world again.

The Japanese aggression has got to be repeatedly exposed and publicized to the world to prevent historical tragedies from recurring. In this regard, two issues of Japanese infamy that bear lasting significance call for attention – [a] the Nanjing Massacre, and [b] Unit 731. They form part of essential historical background to modern day China; and yet people around the world are ill-informed. We shall discuss both in our February 1 and 16 posts, respectively.

—————————————————

ENDNOTES:

[1] See “Why China commemorates its WWII victory” at https://johnmenadue.com/post/2025/08/why-china-commemorates-its-wwii-victory/

[2] For all these years, Japan has steadfastly refused to officially apologise and make reparations. Educated Japanese individuals have called this Japanese conduct shameful and a gross failure to learn from history; they insist that Japan must repent and sincerely apologise before it can build healthy relations with neighbouring countries. See “【短片】【天理不容】岸田政府拒承認侵華罪行 日本商界、學者怒斥可恥!” at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKN-nskYGF0

[3] Prof. Jeffrey Sachs calls Japan’s increasing militarism dangerous, does not make good sense for Japan, and anachronistic in today’s world. His response to Takaichi’s disastrous Taiwan-remark is interesting: “Honestly, Japan should be a lot more careful. It was not China that invaded Japan repeatedly between 1894 and 1945, it was Japan that invaded China repeatedly. So it just seems to me, as a basic measure, Japan should be careful, measured, prudent, and peace oriented with China. And I think the new Prime Minister of Japan got off on the wrong foot. And I hope it was a mistake that won’t be repeated.” See “Jeffrey Sachs: Japanese PM Got Off on the Wrong Foot – YouTube”.

[4] See Fred Zhang, “Democracies Good, China Bad – and history not required” at https://johnmenadue.com/post/2026/01/best-of-2025-democracies-good-china-bad-and-history-not-required/?utm_source=Pearls+%26+Irritations&utm_campaign=7170726031-Daily&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_0c6b037ecb-7170726031-668147987

[5] For discussion on a different tack, an important one no doubt, which involves an insidious collaboration between Japan and the US to secure Taiwan as a key strategic foothold for Pacific control, see “迄今为止对日本此次挑衅中国台湾问题最靠谱的分析!-YouTube” (narrated in English). The analysis says the kingpin in all this is American instigation, without which the Japs would not have the gut to kick up all this dust. But it’s a dangerous game, for if the thesis is accurate, China will take counter-measure at the serious expense of the US.

[6] On the issue of Takaichi’s disastrous Taiwan-remark, Singapore PM Lawrence Wong seemed to have uncharacteristically misjudged its seriousness and flippantly advised China recently to “go easy” on Japan. The Taiwan-issue is China’s redline and no politician can afford to be blasé about it; even the U.S. is treading cautiously in regard to it. George Yeo, a former Singapore Foreign Minister, understands this well. See “在新加坡总理让中国和日本和解忘记历史而被中国批评后,新加坡前外长接受中国媒体的采访直言如果他是中国国政府一员会向日本提出更加明确的要求,直言他们也没有忘记日本对新加坡罪行,这算是派人致歉吗 – YouTube” (narrated in Chinese).

[7] “Victor Gao DESTROYS Western Scholars in Explosive Taiwan Debate – YouTube”.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, January 2026. All rights reserved.

To comment, email jeffangiegoh@gmail.com.