If you offer your food to the hungry

and satisfy the needs of the afflicted,

then your light shall rise in the darkness

and your gloom be like the noonday. [Isaiah 50:8, NRSV]

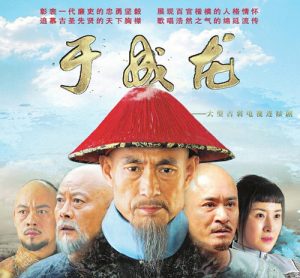

[l] Bronze statue of Yu Chenglong. [R] Poster for new television drama Yu Chenglong [Photo/sxrb.com].

Blessed indeed would be the people of a nation who had in their midst a true gentleman official whose character was as straight as a bamboo stem and for whom wealth and power meant little. Sworn to righteous service to the king and his people, his heart, hollow like a bamboo trunk, would be devoid of worldly ambitions. Integrity, dedication and discipline would be his watchwords. Service, to the very end, would be his life mission. Yu Chenglong was such a man.

A senior government official from the Shanxi province of China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), Yu Chenglong (于成龍, 1617-1684) is also the title of an anti-graft television historical-drama series that comes in the wake of the current severe anti-corruption campaign undertaken by President Xi Jingping’s administration.

“Graft culture” is deep-seated in China. If graft-revelations in contemporary China are shocking, that is in part because the public exposures of graft cases involve such colossal sums that were never before heard. Blinding wealth has been generated in China by recent economic boom. Temptations for corruption are everywhere across the country, from central politburo to mere junior district officials. Fighting tooth and nail against President Xi’s severe anti-corruption campaign, is an interest-based resistance aggressively anchored on strong power bases in politics and finance.

Against that background, this TV series on Yu Chenglong offers the much-needed advocacy on two cardinal principles for the discipline of the Chinese civil servants: one on corruption-free culture, and the other on devotion to duty.

The series pivots on Yu, a civil servant renowned for tenacious integrity and dedication to improving the people’s lives. With discipline and sheer grit, the extent of sacrifice he was willing to make to discharge his duty was astounding. Truly a man of peace without weakness, Yu’s interior strength outflows into his exterior work as a fiercely upright and doggedly diligent civil servant. This inside-outside-unity runs through the entire series. The likes of him amongst the “people’s officials” (天下父母官) was truly rare. Viewers risk being seriously moved and inspired all the way. Episode 33 offers a dramatic sample of his character.

How he acted

Travelling through towns and villages while seriously ill from work-exhaustion (which he hid from the public), this Viceroy of Liangjiang insisted on studying firsthand the harsh conditions of famine and inspecting government relief work. But the degree of devastation was more severe than he imagined. The masses, plagued by perishing hunger, were dropping like flies. And yet, there was an utter lack of concern and assistance from the corrupt government officials charged by the Emperor to coordinate famine-relief. What Yu saw infuriated him. Cut to the heart, he blasted the local official accompanying him on his field trip at Tze-Li:

- As the official in charge of famine relief, how can you be so blatantly irresponsible? If these villagers and those falling dead by the wayside are your parents, brothers and sisters, would you treat them with such inhuman disdain? Answer me! Answer me! Are you not hurting inside, when you see such devastation everywhere we go? This famine has run so deep, and yet all of you government officials are indifferent. Where is justice? Where is your conscience? … You don’t have to be sorry to me, but you ought to be sorry to the tens of thousands of ordinary people under your care. You ought to be sorry to the Emperor who placed his trust in you.

The official acknowledged his failures, but added that upon the death of the local governor, repeated crisis-reports and pleas for urgent food-relief solicited no response from the central government. Foot-dragging happened at the centre, not at the periphery where suffering cut deep. What could a division-four regional official do? One by one, district officers came forth to report figures of famine-death and counting, attributing in unison the root cause to failure of the imperial central administration to respond to repeated regional pleas for urgent relief.

Yu asked where in Tze-Li could one find any food at all to feed the hungry. The shocking reply: there was food only in the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot.

Yu knew at once what he had to do. He ordered the opening of the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot at once. But none dared to move, for there was a problem beyond the power of any officer of any rank: Imperial law strictly required the Emperor’s prior consent before food-distribution from the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot, a breach of which was punishable by death.

The situation clarified, Yu knew what he must do. He ordered the immediate opening of the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot. He would take full responsibility for the breach of imperial law. Lives of the people were more important than the emperor’s law. For the sake of saving lives, he would bear all consequences himself. District officers pleaded with him to reconsider his death-wish. He rejected their plea. His advisors pressed some cogent arguments on opportunity costs against him:

- “Look, tens of thousands of the poor people will continue to need you to champion their cause. What good are you doing for them if you should die now over this rush decision?”

To which Yu, resolute in giving concrete help in the here and now, replied: “What good will I be to those who died on my watch?” Futuristic benefits would simply be too late for them. To him, saving the people’s lives right now must rank before saving his own. Besides, a systemic error in protecting the imperial food reserve when people were dying from hunger was a mockery he would not be a part of. If the only way to prevent further deaths was to open the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot, then it must be done [拯救百姓的生命, 只能私開皇倉放糧].Against the imperial commissioner’s warning of the death penalty, Yu’s reply sealed the immediate existential salvation of the masses. If he should die on account of it, so be it. Duty and conscience came first. He was fearless.

- “Just as I have decided to privately authorize the opening of the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot, I no longer fancy saving my own life anymore.”

He would feed the hungry at the price of his own life. Such was the integrity of the man! (一顆腦袋換來無數飢民飽餐一頓,真是個不可多得的父母 官啊.)

How the Emperor Reacted

On hearing of YU’s blatant action, Emperor Kangsi spoke out at his morning cabinet conference:

- Yu Chenglong opened the Emperor’s Reserved Food Depot without permission. What gave him that kind of courage? In the Province of Tze-Li, there isn’t a single area that is famine-free, that has not seen people dying of perishing hunger. Before the previous governor of Tze-Li passed away, he had already reported the critical situation to the imperial court. Why was there such protracted delay? Must we wait for people to die before we take any action? Now I see with such clarity. For all this assembly of scholarly and military cabinet ministers, none is comparable to Yu Chenglong who alone dares to petition on behalf of the suffering masses, who alone has no fears of losing his job and his head, and who alone dares to resonate my heart and my virtue.

Upon hearing these words from the Emperor, the corrupt prime minster dropped to his knees and accepted his failure. To him the Emperor said with disdain, “Then, you may remain on your knees!”

Like Jesus the Good Samaritan, Yu took an active stand against the dark enemy of all that is good. His love persisted in the face of grievous suffering. He loved to the end, despite the evil corruption poisoning the entire system. He lived a frugal, simple and upright life, never stopped working and, after 23 years’ of relentless public service, upholding justice (Christians often prefer the term “righteousness”) and loathing evil, died in office out of exhaustion.

Openly lamenting Yu Chenglong’s death, the Emperor stressed his exemplary way of servant-leadership in public service as a spirituality worthy for his entire cabinet to emulate.

Ranking first in the order of civil service, the Emperor insisted, was clean governance. He who exemplified this virtue and deserving of recognition for all to emulate from was none other than Yu Chenglong. Relentless in guarding personal honour and dignity, he toiled and moiled, and became the model all must learn from. His steadfastness exceeded all civil servants. In his humble abode, nothing of material value remained. Like a refreshing breeze, all that he left behind was a lasting legacy of remarkable virtues that was royally commended as defining model for all. In modesty and uprightness, Yu Chenglung had ministered in the civil service. Henceforth, he would be proclaimed as the foremost upright official of the kingdom (一 代 清 官 廉 吏, 天下廉吏第一).

Happy Gawai to all who celebrate the festival!

Post-script: Under its current anti-corruption drive, Shanshi Province has ordered the renovation of Yu Chenglong’s tomb, “as a constant reminder for cadres to remain beyond reproach”.

[L] Yu Chenglong tomb. [R] Foremost upright official of the kingdom plaque.

Copyright © Dr. Jeffrey & Angie Goh, June 2020. All rights reserved.

You are most welcome to respond to this post. Email your comments to jeffangiegoh@gmail.com. You can also be dialogue partners in this Ephphatha Coffee-Corner Ministry by sending us questions for discussion.